New map restores Native names to northern Minnesota

The names of many lakes, rivers and cities across northern Minnesota have roots in the Ojibwe language — Bemidji, for example, is derived from the word bemijigamaag meaning “Lake with crossing waters” — a reference to how the Mississippi River flows across Lake Bemidji.

But the names of many more places have been lost to history.

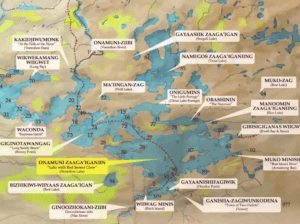

Now, a partnership between the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, the nonprofit Ely Folk School, and several volunteer artists is seeking to change that. This week they’re unveiling a map that features more than 100 Ojibwe place names from across the Band’s territory, including names uncovered in diaries stored in the Smithsonian dating back to the 1800s.

“This project underscores our voice and our history in the region,” said Bois Forte Tribal Chair Cathy Chavers. “This map will serve as a tribute to all who came before us and to the future generations as well.”

Inspired by canoe trip

The project, believed to be the first of its kind in the state, was inspired by a trip people from the Folk School took to the Lac la Croix First Nation in Ontario in 2019. A group paddled a flotilla of hand-built birchbark canoes across the Boundary Waters to the Band’s reserve for an annual powwow.

While there, Lac La Croix residents shared a map they had created of Quetico Provincial Park. It showed the original Native names of lakes and other significant places, with their meanings and some of the stories behind the names.

“And we wondered if something similar existed for our side of the border,” said explorer and dog-sledder Paul Schurke, an Ely Folk School board member who was on that trip.

It turns out, something did — but they had to do some digging to find it. The Ojibwe, or Anishinaabe language is primarily oral, so Ojibwe people didn’t keep written records of place names.

But in the 1870s, a missionary in northern Minnesota named Joseph Gilfillan, who spoke fluent Ojibwe, painstakingly recorded in his diaries all the names he could find. And those diaries are still in the archives at Smithsonian, “the largest single collection of names for northern Minnesota,” Schurke said.

Others followed in his footsteps, including anthropologists and a geologist named Warren Upham, whose 800-page “Minnesota Geographic Names,” published in 1920, is one of the largest collections of Native names compiled in the country.

But not much was ever done with those records, until now. The folk school and the Bois Forte Band teamed up with artist Louise Isham, who is an enrolled band member, and artisanal map maker Keith Myrmel to create the map.

‘Lyrical, descriptive, poetic names’

It features 106 names of places around the Bois Forte homeland, from Lake Vermillion to Nett Lake.

Schurke describes them as “very lyrical, descriptive, poetic names.” They include lakes and rivers, historic trading sites and village locations.

The Ojibwe name for Lake Vermilion, for example, — Onamani — means “Lake with red sunset glow.” The name for the lake’s Bystrom Bay, Gagons-ibi-madage-winik, means “Place where the young porcupines swim.”

The map includes sidebars with historical information about the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, its chiefs, and traditions.

According to Rick Anderson, a folk school board member who is also enrolled in the Bois Forte Band, the groups also hope to produce an online version of the map. He said it will include links to pronunciations of the Ojibwe names and traditional stories about the places.

Anderson said he’s always been bothered by phrases like “untrammeled by man,” which was included in the federal legislation that created the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Because “man” has lived here for thousands of years, Anderson said. And to exclude indigenous history and continued presence “was a disservice to the Native people of the region,” he added.

This map “illustrates the extent and the reach and the understanding and the love of the region by the Anishinaabe people,” Anderson said.

Urgent need

Anderson and others consulted with Ojibwe elders for help producing the map. One of their primary sources, Gene Goodsky, died this past year, shortly after he gave his input on the map. That underscores how important it is to collect these names quickly, Anderson said.

“We don’t have a written language. So it’s hard to preserve. As the elders have been passing away, fewer and fewer have any knowledge of the ancestral names. So it was critical that we did this now.”

The map will be unveiled at the Bois Forte Heritage Center and Cultural Museum on Wednesday Nov. 30. Copies of the map’s first limited edition printing will be available through an Ely Folk School fundraiser.

The hope next is to expand the map to include all of the Arrowhead region, including the more than 1,000 lakes within the Boundary Waters.

“It was kind of a standing joke in the Boundary Waters that so many of the lake names there are named after lumberjacks or their girlfriends,” said Schurke. “Too many original descriptive lake names were replaced with names of lumberjacks’ love interests.”

Editor’s note (Nov. 29): A previous version of this story incorrectly named the northern Minnesotan missionary. It has been updated.

(source:https://www.mprnews.org/story/2022/11/27/new-map-restores-native-names-to-northern-minnesota)